Introduction

He was, in the same person, austere and genial, dignified and playful… cruel and merciful, and always in all things changeable

Historia Augusta, Hadrian 14.11, Loeb Classical Library

This exhibition brings together, for the first time, the only three bronze portraits of the Roman emperor Hadrian to have survived

from antiquity. Seemingly alike, though each with its own unique set of characteristics, the portraits highlight the multifaceted and

contradictory aspects of Hadrian's character.

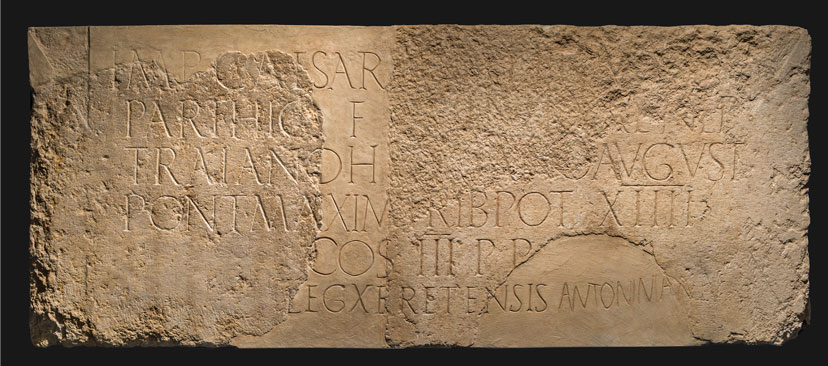

Hadrian – Publius Aelius Hadrianus – was one of Rome's most important emperors. Born in 76 CE, he was forty-one years of age when he came to the throne in 117 CE. He began his reign at a time of acute military crisis, when the Roman Empire was the largest it had ever been. Through tremendous personal effort and far-reaching administrative, economic and military reforms, Hadrian stabilised the empire, ensuring its survival for centuries to come. He travelled widely through nearly all the provinces, from Britain to Africa, from Spain to Judea.

With his abundant energy, keen intellect, and wide-ranging interests, Hadrian is considered one of the Roman Empire's more enlightened rulers. However, his ruthless suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt and the subsequent destruction of Judea make him a much-loathed figure in Jewish history.

Photographs © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Elie Posner, unless stated otherwise